Gabriel García Márquez’s Formative Reading List: 24 Books That Shaped One of Humanity’s Greatest Writers

by Maria Popova

“Life is not what one lived, but what one remembers and how one remembers it in order to recount it.”

The most reliable portal into another’s psyche is the mental library of that person’s favorite books — those foundational idea-bricks of which we build the home for our interior lives, the integral support beams of our personhood and values. And who doesn’t long for such a portal into humanity’s most robust yet spacious minds? Joining history’s notable reading lists — including those of Leo Tolstoy,Susan Sontag, Alan Turing, Brian Eno, David Bowie, Stewart Brand, Carl Sagan, and Neil deGrasse Tyson — is Gabriel García Márquez.

The most reliable portal into another’s psyche is the mental library of that person’s favorite books — those foundational idea-bricks of which we build the home for our interior lives, the integral support beams of our personhood and values. And who doesn’t long for such a portal into humanity’s most robust yet spacious minds? Joining history’s notable reading lists — including those of Leo Tolstoy,Susan Sontag, Alan Turing, Brian Eno, David Bowie, Stewart Brand, Carl Sagan, and Neil deGrasse Tyson — is Gabriel García Márquez.

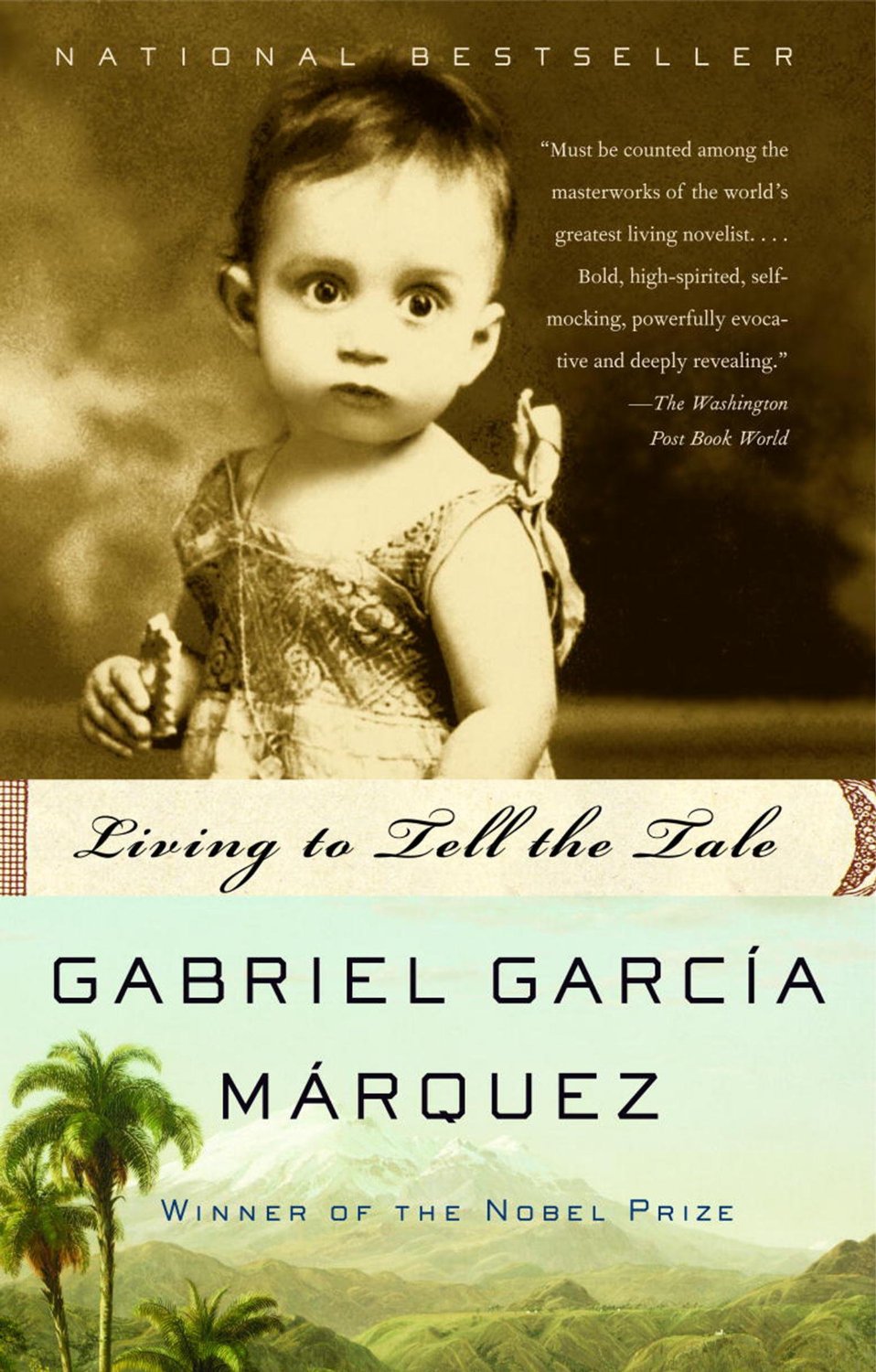

Woven into Living to Tell the Tale (public library) — the autobiography that gave us the emboldening story of García Márquez’s unlikely beginnings as a writer — is the reading that shaped his mind and creative destiny. “Life is not what one lived, but what one remembers and how one remembers it in order to recount it,” García Márquez writes, and kindred-spirited readers instantly know that memorable books are the existential markers of life’s lived and remembered chapters.

Here are the books that most influenced García Márquez — beginning with his teenage years at boarding school, of which he recalls: “The best thing at the liceo were the books read aloud before we went to sleep.” — along with some of the endearing anecdotes he tells about them.

- The Magic Mountain (public library) by Thomas Mann

- The Man in the Iron Mask (free ebook | public library) by Alexandre Dumas

- Ulysses (free ebook | public library) by James Joyce

- The Sound and the Fury (public library) by William Faulkner

- As I Lay Dying (public library) by William Faulkner

- The Wild Palms (public library) by William Faulkner

- Oedipus Rex (free ebook | public library) by Sophocles

- The House of the Seven Gables (free ebook | public library) by Nathaniel Hawthorne

- Uncle Tom’s Cabin (free ebook | public library) by Harriet Beecher Stowe

- Moby-Dick (free ebook | public library) by Herman Melville

- Sons and Lovers (free ebook | public library) by D.H. Lawrence

- The Arabian Nights: Tales from a Thousand and One Nights (free ebook |public library)

- The Metamorphosis (public library) by Franz Kafka

- The Aleph and Other Stories (public library) by Jorge Luis Borges

- The Collected Stories (public library) by Ernest Hemingway

- Point Counter Point (public library) by Aldous Huxley

- Of Mice and Men (public library) by John Steinbeck

- The Grapes of Wrath (public library) by John Steinbeck

- Tobacco Road (public library) by Erskine Caldwell

- Stories (public library) by Katherine Mansfield

- Manhattan Transfer (public library) by John Dos Passos

- Portrait of Jennie (public library) by Robert Nathan

- Orlando (public library) by Virginia Woolf

- Mrs. Dalloway (public library) by Virginia Woolf

The thundering success of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain … required the intervention of the rector to keep us from spending the whole night awake, waiting for Hans Castorp and Clavdia Chauchat to kiss. Or the rare tension of all of us sitting up on our beds in order not to miss a word of the disordered philosophical duels between Naptha and his friend Settembrini. The reading that night lasted for more than an hour and was celebrated in the dormitory with a round of applause.

One day Jorge Álvaro Espinosa, a law student who had taught me to navigate the Bible and made me learn by heart the complete names of Job’s companions, placed an awesome tome on the table in front of me and declared with his bishop’s authority:“This is the other Bible.”It was, of course, James Joyce’s Ulysses, which I read in bits and pieces and fits and starts until I lost all patience. It was premature brashness. Years later, as a docile adult, I set myself the task of reading it again in a serious way, and it not only was the discovery of a genuine world that I never suspected inside me, but it also provided invaluable technical help to me in freeing language and in handling time and structures in my books.

I became aware that my adventure in reading Ulysses at the age of twenty, and later The Sound and the Fury, were premature audacities without a future, and I decided to reread them with a less biased eye. In effect, much of what had seemed pedantic or hermetic in Joyce and Faulkner was revealed to me then with a terrifying beauty and simplicity.

[The writer] Gustavo [Ibarra Merlano] brought me the systematic rigor that my improvised and scattered ideas, and the frivolity of my heart, were in real need of. And all that with great tenderness and an iron character.[…]His readings were long and varied but sustained by a thorough knowledge of the Catholic intellectuals of the day, whom I had never heard of. He knew everything that one should know about poetry, in particular the Greek and Latin classics, which he read in their original versions… I found it remarkable that in addition to having so many intellectual and civic virtues, he swam like an Olympic champion and had a body trained to be one. What concerned him most about me was my dangerous contempt for the Greek and Latin classics, which seemed boring and useless to me, except for theOdyssey, which I had read and reread in bits and pieces several times at the liceo. And so before we said goodbye, he chose a leather-bound book from the library and handed it to me with a certain solemnity. “You may become a good writer,” he said, “but you’ll never become very good if you don’t have a good knowledge of the Greek classics.” The book was the complete works of Sophocles. From that moment on Gustavo was one of the decisive beings in my life, forOedipus Rex revealed itself to me on first reading as the perfect work.

[Gustavo Ibarra] lent me Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables, which marked me for life. Together we attempted a theory of the fatality of nostalgia in the wanderings of Ulysses Odysseus, where we became lost and never found our way out. Half a century later I discovered it resolved in a masterful textby Milan Kundera.

I even dared to think that the marvels recounted by Scheherazade really happened in the daily life of her time, and stopped happening because of the incredulity and realistic cowardice of subsequent generations. By the same token, it seemed impossible that anyone from our time would ever believe again that you could fly over cities and mountains on a carpet, or that a slave from Cartagena de Indias would live for two hundred years in a bottle as a punishment, unless the author of the story could make his readers believe it.

I never again slept with my former serenity. [The book] determined a new direction for my life from its first line, which today is one of the great devices in world literature: “As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.” [I realized that] it was not necessary to demonstrate facts: it was enough for the author to have written something for it to be true, with no proof other than the power of his talent and the authority of his voice. It was Scheherazade all over again, not in her millenary world where everything was possible but in another irreparable world where everything had already been lost. When I finished reading The Metamorphosis I felt an irresistible longing to live in that alien paradise.

It was the first time I heard the name of Virginia Woolf, whom he [Gustavo Ibarra] called Old Lady Woolf, like Old Man Faulkner. My amazement inspired him to the point of delirium. He seized the pile of books he had shown me as his favorites and placed them in my hands.“Don’t be an asshole,” he said, “take them all, and when you finish reading them we’ll come get them no matter where you are.”For me they were an inconceivable treasure that I did not dare put at risk when I did not have even a miserable hole where I could keep them. At last he resigned himself to giving me the Spanish version of Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, with the unappealable prediction that I would learn it by heart.[…]I went [home] with the air of someone who had discovered the world.

Living to Tell the Tale is a glorious read in its entirety — the humbling and infinitely heartening life-story of one of the greatest writers humanity ever produced. Couple it with Old Lady Woolf on how one should read a book.

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario